Lost in Translation: Finding a Voice in a German Campus Radio

Feature . MediaThe first thing I didn’t understand was a joke.

The speaker made a remark about student radio culture. The room laughed immediately. I smiled a second too late, trying to catch the tone rather than the meaning. Around me, pens were already moving again, notebooks filled with bullet points and arrows. The information session for M94.5 had started at 6 p.m. sharp on October 21, 2025, just as announced. What I had misunderstood was the language.

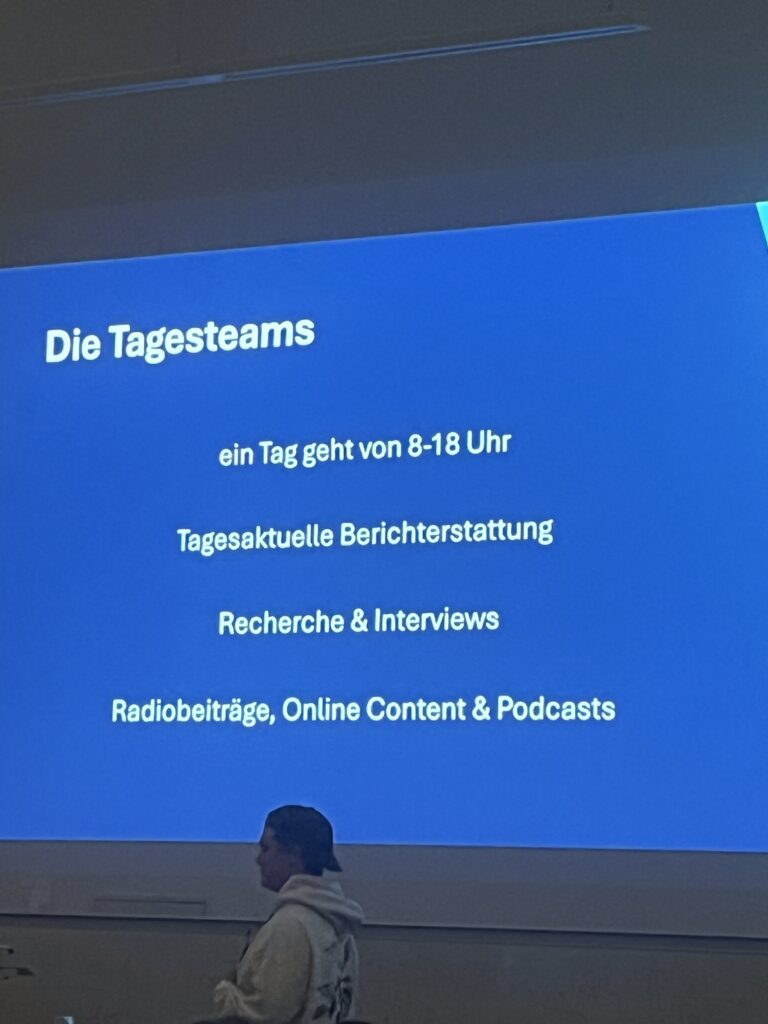

The presentation was in German. I had never really considered that it could be otherwise, I had assumed, almost instinctively, that an information session aimed at all students would be held in English. Even the slides were in German. They were meant to explain how M94.5 works: the different editorial sections, the training process, and the path from volunteer to host. I recognized a few words (Redaktion, Sendung) but not enough to follow the logic. Ironically, this information session was designed to lower the barrier to entry for new contributors. Instead, it quietly revealed another one.

Photo 1 : Slide presentation from the conference on 21/10 taken by @liamcapgras

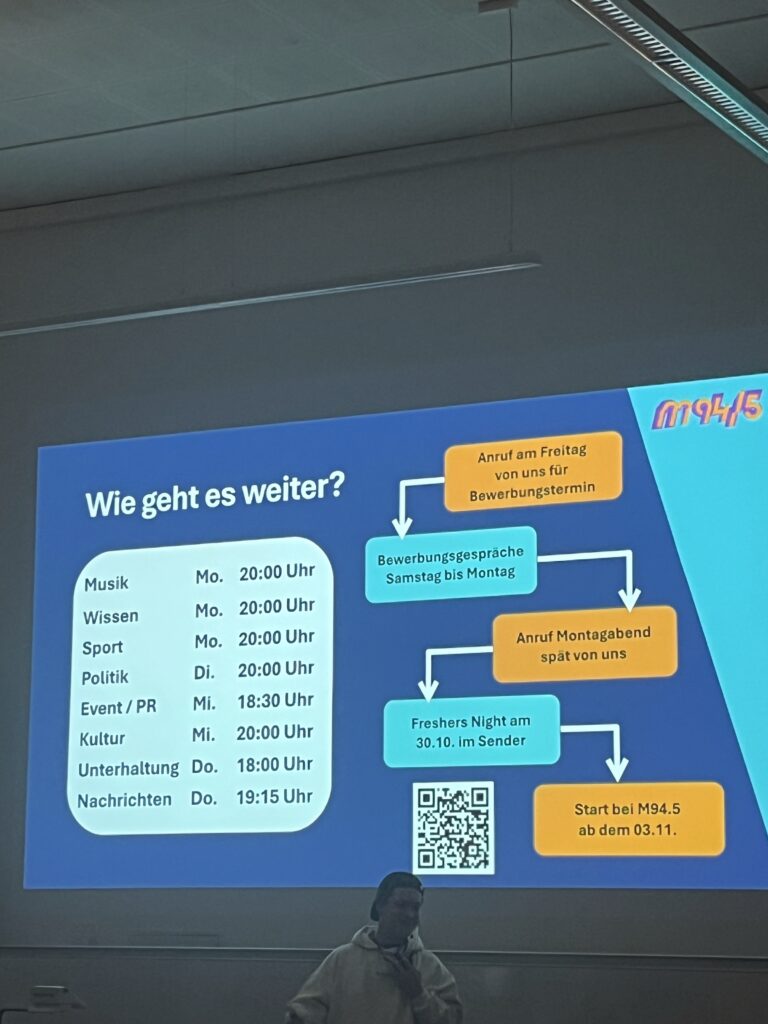

When the presentation moved on to the station’s structure (news, music programming, and cultural formats), the speakers clarified when each section met and what kind of availability was expected to join them. I noted down times and titles without fully understanding what distinguished one section from another. I knew I was interested. I just didn’t know where I would fit. Not speaking German, I started clinging to fragments. When I saw the word “Tag” appear on the slides, I remembered it meant “day,” which led to a series of small, personal deductions. I had already discovered döner kebabs by then, so for a moment I convinced myself that Donnerstag might be the “day of döners,” an unexpected, if slightly hopeful, gastronomic insight. I was pulled back into the room by laughter, another joke I only understood a few seconds too late.

Photo 2 and 3 : Slide presentation from the conference on 21/10 taken by @liamcapgras

What I experienced that evening is not unusual. Munich hosts tens of thousands of international students, they do integrate them very well, as English is well spoken here, yet a student radio station like M94.5 remains largely oriented towards German-speaking content, even when they explicitly seek new contributors and are very open to internationals. The promise of openness is real, but it is not always accessible in the same way to everyone.

Campus radio stations are often described as laboratories: places for experimentation, civic engagement, and student participation. M94.5 presents itself as a platform “by students, for students,” rooted in the city and in university life. But language quietly redraws the boundaries of who those students are. When access to information and editorial structures (like the entry questionnaire) are communicated mainly in German, international students are not formally excluded, yet they can feel effectively filtered out at the very first step.

This matters because campus radio is not just another media outlet. It is often a first point of contact with local culture, a space where students learn how media works from the inside, and a place where communities take shape. For international students, it can be a powerful tool of integration or a reminder of distance. That evening, the issue was not a lack of motivation or interest. It was the absence of a linguistic bridge.

Munich is one of Germany’s most international student cities. Across institutions like LMU and TUM, international students represent roughly one-fifth of the total student population. English is the working language of many degree programs, especially at the master’s level. In other academic contexts, particularly in internationally oriented institutions such as my home university, Emlyon, the inclusion of international students has become an explicit institutional objective, one that student organizations are increasingly expected to address in concrete terms.

At the same time, several contributors acknowledge that English already circulates informally within the station. Music shows regularly feature English-speaking artists. Interviews are sometimes conducted in English when an international volunteer is here. Online formats, podcasts, social media posts, and written descriptions tend to be more flexible than FM broadcasting. In practice, M94.5 already operates across languages, even if German remains the default.

This creates a tension rather than a contradiction. The challenge is not whether M94.5 should “switch” to English, but how it might integrate English-language content strategically without losing its identity. Language, in this sense, becomes less a binary choice than a matter of format and context.

Media researchers have long shown that language is not only a tool of communication but also a gatekeeping mechanism that shapes participation and belonging in public spaces. In student media, this gatekeeping is rarely intentional. It emerges from habits, workflows, and assumptions about who the audience is.

After the conference, I went back to the M94.5 website. I scrolled through program descriptions, listened to a few shows, and tried to map the structure I had only partially understood on the slides. Certain sections seemed more open than others. Some voices sounded familiar, others distant. I started recognizing names.

One of them was André, whose work appeared repeatedly across different formats, as he is the head of music publishing. A few days later, I drafted a message. I hesitated longer than I should have, then sent it. I explained my situation, my interests, and my language limits. The reply came back quickly, friendly, and open. We agreed to talk.

This is where the story shifts. Not because the problem disappears, but because it becomes tangible. The question is no longer whether international students can find their place at M94.5, but under what conditions. Language is one of them, not as an obstacle to be removed entirely, but as a parameter to be negotiated.

That evening, I did not understand the joke. But I understood something else: inclusion often begins long before the microphone is switched on.

Leave a Reply