Reportage about the Oktoberfest: Traditional celebration, or an overpriced festival?

Culture . Food . Germany . TravelHey everyone! I’m back with another post from my Professional Communication course at LMU. For this assignment, we were asked to write a reportage about a topic in our environment that raises a question or shows an issue. Since I’m currently on exchange in Munich, I decided to finally go to Oktoberfest, something I had wanted to experience for years. I went with a couple of international friends, and we spent the last day of the festival exploring the traditional and the more modern parts. Here’s my take on the experience, and the question it left me with about tradition, tourism, and the price of celebration!

I remember the first time I heard about Oktoberfest. It was during one of my first German classes in high school. Our form master was also our German teacher, and one day she showed us pictures and short videos of Germany: people in traditional clothes, long wooden tables, music, beer, and crowds celebrating together. What stayed with me was not the beer, but the atmosphere. People looked happy, connected, and open to visitors from all over the world.

With my classmates, we soon started joking about it. Since we had a German teacher as our form master, we kept asking her if she could take us to Germany on a school trip, or maybe even to the Oktoberfest. Of course, it never happened. It would have been too expensive, we did not speak German well enough, and school life was full of other priorities. Over time, Oktoberfest became an inside joke in our class: something we talked about without truly expecting to experience.

After high school, the joke slowly turned into reality. I spent some time in Germany through an international program and later returned for an Erasmus semester in Munich. Still, Oktoberfest remained unfinished business. Last year, I remembered it too late. Despite its name, Oktoberfest ends in early October, something I only realized when it was already over.

This year, the timing finally worked. I arrived in Munich on the first of October, just before the final weekend of the festival. Together with two international friends: one from the Czech Republic and one from France, I decided that we would finally go. None of us had been there before. We had seen the images, heard the stories, and laughed about the stereotypes. Now, we wanted to see it ourselves.

Even before reaching the festival, Oktoberfest seemed to be everywhere. At the airport, people in Lederhosen and Dirndls waited at the gates. On the train into the city, groups were already drinking beer and singing. Airlines and brands openly promoted Oktoberfest, turning Bavarian tradition into a recognizable global image. At first, this added to my excitement. The openness felt welcoming.

But small details raised questions. Many traditional clothes looked more like costumes than something worn with meaning. Cheap Dirndls, Lederhosen combined with sneakers, outfits clearly chosen for photos. At one point, I started a conversation in German with someone, only to realize they were American tourists who did not speak any German at all. They were friendly but completely disconnected from the culture they were visually representing.

Until then, Oktoberfest had felt more like a mood than a place. Munich itself had become a festival city. Our actual visit came only on the last Sunday. Together with our German friends, we took the U-Bahn to Theresienwiese. When we stepped out, the mood shifted. Police officers were everywhere, bags were checked, streets blocked. It was reassuring and unsettling at the same time. Oktoberfest was not only a celebration, it was a controlled space. A few days before they even had to close the Wiesen, because there was a bomb alarm. But our curiosity was stronger than our fear of danger.

We started at the Oide Wiesn, the traditional part of the festival. The music was purely Bavarian, the dances old-fashioned, the crowd older and calmer. Many people seemed to know each other. It felt authentic but a bit distant. We watched more than we participated. We did not understand the songs or the fast Bavarian accents. Still, this place felt closest to the Oktoberfest I had imagined for years.

Source: Author’s own photograph

Then came the prices. A single Maß of beer cost sixteen euros. Food quickly reached twenty euros or more. Even without having to pay for accommodation, the evening became expensive. By the end of the night, we had spent hundreds of euros without buying very much.

My Czech friend laughed in disbelief. In her country, beer costs a fraction of the price, and the quality is not worse. Still, she admitted the Bavarian beer was good. Enjoying it, however, felt like a careful decision. The same applied to the amusement rides. In the end, we tried only one. Oktoberfest offered many experiences, but only if you could afford them.

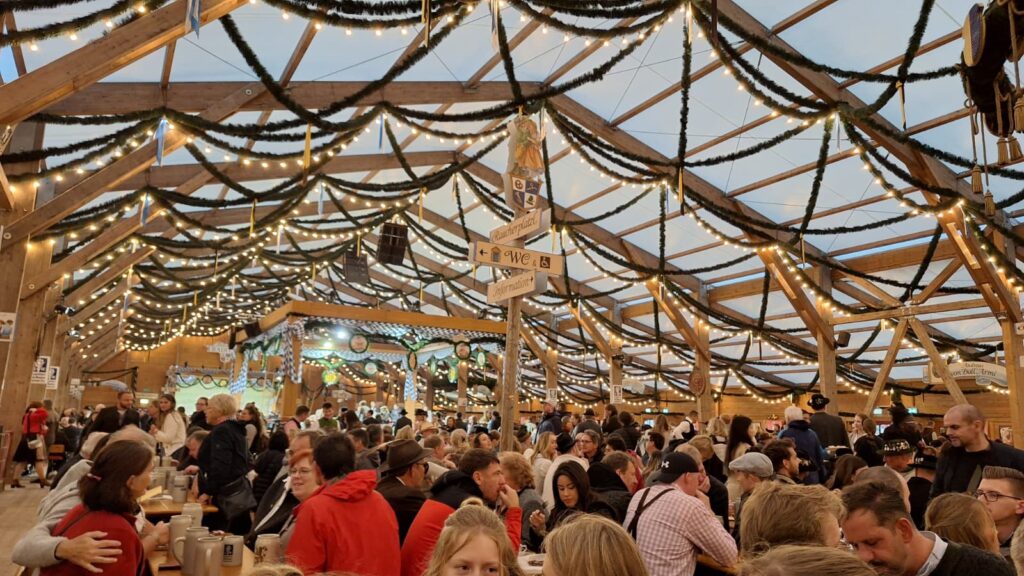

Later, we moved to one of the younger tents. The contrast was immediate. It was loud, crowded, and full of energy. English dominated the conversations. Whenever we tried to speak German, people switched to English. Many visitors were tourists, and songs like Sweet Caroline and Country Roads filled the space.

Source: Author’s own photograph

The atmosphere was welcoming, and we enjoyed ourselves. But something felt missing. This version of Oktoberfest could have taken place almost anywhere. Standing in the crowd, I wondered whether the openness was still about sharing culture, or mainly about selling it.

Toward the end of the evening, staff handed out sparklers. The lights dimmed, people stood closer, and the last songs played. Even for first-time visitors, the moment felt nostalgic. This was the final night of Oktoberfest, and everyone seemed to know it.

When we left, the night felt quieter. Tired, slightly dizzy after a few beers, we walked toward the U-Bahn, talking about prices, tourists, and authenticity. Someone said it was a pity we had not worn traditional clothes. Another answered that renting them would have been expensive. I realized I had felt unsure about it from the beginning. I am not Bavarian, and wearing their clothes without fully understanding them did not feel right.

At the platform, one of my friends mentioned a smaller spring festival: similar, less crowded, more local. We agreed to go next time. Maybe then, with more understanding, we would wear the traditional clothes.

The train arrived, the doors opened, and the crowd pushed forward. Behind us, the noise of Oktoberfest gradually faded away and slowly moved on.

So this was my reportage on Oktoberfest, I hope it helped you to understand some social, economic, and cultural questions about this event. And I would just add, that even if this reportage might have felt a bit negative, the Oktoberfest is actually a great adventure, what you should try at least once in your life. See you next time!👋

Leave a Reply