The Future of Journalism: Opportunities and Challenges of AI-Driven Innovation

UncategorizedBy Minjing Zhou

From automated writing and algorithmic recommendations to fake news detection, AI is not only boosting efficiency but also raising complex issues regarding ethics, public interest, and professional boundaries.

From a structural-functionalist perspective, journalism serves four key functions: information provision, opinion formation, social integration, and power oversight. AI clearly enhances the efficiency of information production. For instance, financial briefs, weather reports, and sports summaries can now be generated automatically, freeing journalists to focus on investigative and human-interest reporting.

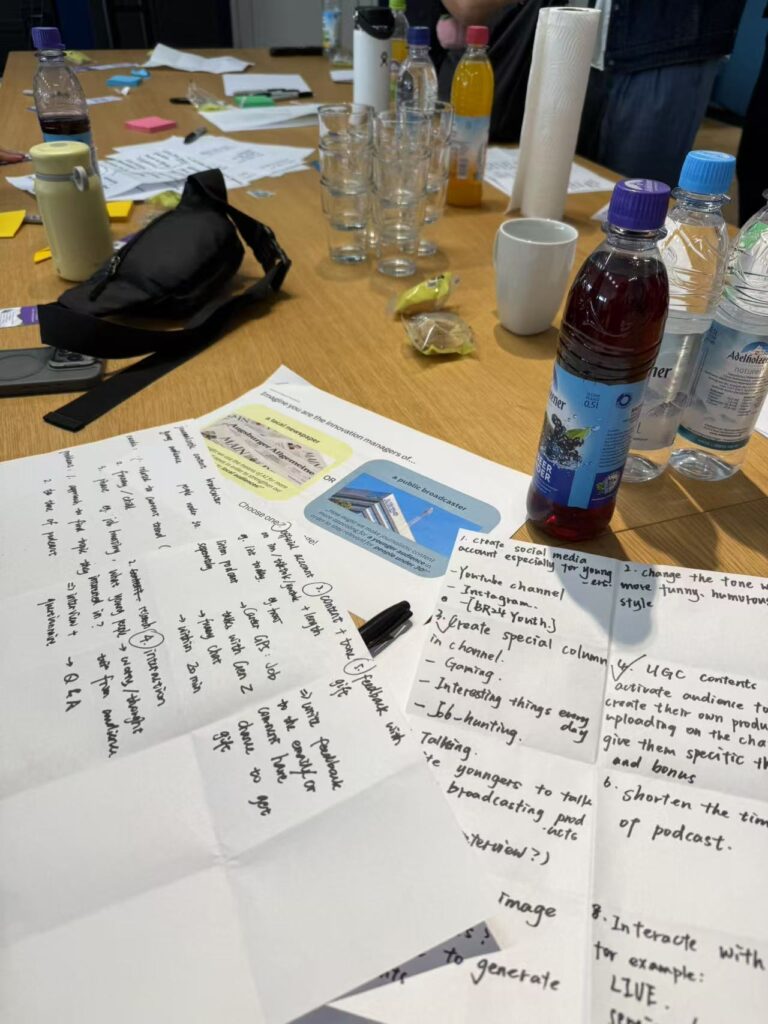

During my fieldtrips in Munich, I observed that some media institutions are actively exploring AI-driven innovation. Media Lab Bayern already thinks how to build AI-powered tools like automated content generation, multilingual translation, and personalized podcast recommendations. In more traditional outlets like Süddeutsche Zeitung, AI is mainly used for tasks like archiving, data visualization, and social media tracking. Yet editors emphasized that AI should remain a supporting tool—not a decision-maker in journalistic judgment.

Meanwhile, many Chinese media are building their own AI “brands.” Xinhua launched a virtual news anchor Xin Xiaowei, while People’s Daily has used AI-generated hosts in short-form video content. These efforts are not just about efficiency—they aim to create recognizable AI personas that enhance communication and influence. On the other hand, some outlets like The Financial Times explicitly prohibit AI-written news, citing concerns about truth and credibility. These examples reflect how AI adoption is shaped by cultural and institutional norms.

However, AI is not merely a tool for efficiency. Its application in algorithmic distribution and user profiling has deeply changed how audiences interact with news. Recommendation systems personalize news content to increase engagement and time-on-site, but they also exacerbate echo chambers and filter bubbles. This means that audiences are increasingly exposed only to information they already agree with, leading to public polarization. These effects challenge Habermas’s concept of the public sphere—a space for rational debate and democratic discourse. While AI operates on personalization, journalism’s duty is to serve the public interest.

Therefore, future innovation in journalism should not stop at technical optimization. It must aim at strengthening publicness. Some media organizations are using AI to track the spread of misinformation or assist in real-time fact-checking. Others are developing diversity-aware recommendation algorithms that intentionally introduce dissenting or unfamiliar perspectives to break the cognitive loop. These efforts suggest that AI can serve as more than a content carrier—it may become an assistant to the “guardians of pluralism.”

At the same time, AI poses pressing ethical concerns, especially regarding transparency and accountability. When AI is involved in news selection, writing, or editorial decision-making, who is responsible if something goes wrong? The rise of deepfakes has made it harder to distinguish between truth and fabrication, undermining public trust. These challenges show that institutional safeguards must evolve alongside technological innovation.

In conclusion, AI offers powerful momentum for journalism’s future—but it should empower, not replace, the human journalist. The real question is not how fast machines can write, but whether we can use AI to build a more diverse, truthful, and socially responsible media ecosystem.

Leave a Reply