When Image Becomes Power

Culture . Media . Media influence . Opinion piece . Society

In early 2026, South Korean media reported that the National Tax Service (NTS) had levied approximately 20 billion KRW (roughly €14 million EUR) in additional taxes and penalties on actor and singer Cha Eun-woo. This figure ranks as the 6th largest individual tax evasion case reported globally—marking the largest tax surcharge in the history of the Korean entertainment industry. (Source: News1) While Cha’s representatives have filed for a formal review, asserting that there was no intentional evasion, the scale of the surcharge has ignited a fierce debate. In a society where celebrities are often held to the highest moral standards as “public figures,” this case has shifted from a simple legal dispute into a broader critique of celebrity power and social responsibility.

“Face Genius.” “Um-chin-ah.(The Perfect Son Your Mother Always Brags About)“ In South Korea, these aren’t just flattering nicknames—they were the very definitions of Cha Eun-woo. For years, his flawless appearance and upright image earned him an almost untouchable level of public trust. However, recent allegations of a 20-billion-won tax surcharge have sent shockwaves through this carefully built image. The resulting public fury isn’t just about the staggering amount of money. At the root of this fury lies a fundamental skepticism toward the disproportionate power we grant celebrities and the glaring lack of public responsibility that follows.

In Korean society, celebrities are consumed not merely as entertainers, but as “public figures.” This is because public affection translates directly into immense wealth and power. The case of Yoo Seung-jun (Steve Yoo) remains a stark example of this. The public turned its back on him not just because he avoided military service, but because the fame and fortune he enjoyed were granted under the unspoken premise that he would fulfill his duties as a citizen. The moment he shirked that duty, the public revoked his “license” to profit within Korea.

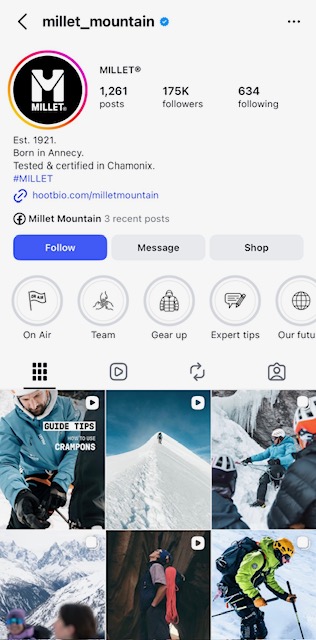

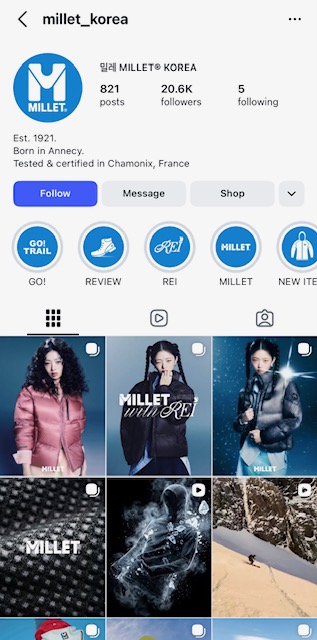

Interestingly, this celebrity-centric culture is not a global norm. Walking through the streets of Germany, I encountered a very different scene. In European advertisements—especially those in the Munich U-Bahn—celebrity faces rarely dominate the space. Often, there is no model at all, or if there is, they play a secondary role to explain the product’s function. The focus remains strictly on the product’s intrinsic value. Korea, by contrast, presents the opposite. Famous celebrities occupy the entire frame, and at times, their image is emphasized more than the product itself. In this structure, the celebrity becomes the brand and the power.

Ultimately, the fury surrounding Cha Eun-woo’s tax case is closer to a resistance against an imbalanced social structure where one can amass unimaginable wealth “simply because they are handsome.” In a society where celebrities are deified and capital is concentrated in their hands, the public feels more than just deprivation—they feel betrayed when those same icons attempt to evade even the most basic communal duty of paying taxes.

Consumers must now question the way they consume celebrities. Are we looking at the essence of a product, or are we buying the projected image of an idol? If the excessive power concentrated in celebrities is undermining the value of fairness, then public outrage is not just a criticism of one individual; it may be a self-purifying reaction intended to correct the distorted consumption structures of modern celebrity culture.

Leave a Reply